Kōrero with a Creative: Rex Letoa-Paget

Kia ora Rex, can you tell me about yourself and your new book, Manuali'i—Bird of the Gods?

I'm of Samoan and Danish ancestry, born and raised in Aotearoa. I identify as fa'afatama or trans masculine. I'm a creative writer and poet, and I love storytelling, which has many forms. Storytelling is an important way forward for the arts and the future we desperately need.

Manuali'i was born from love and grief. I was moving through a lot of different periods and kinds of grief, heartbreak and the loss of a loved one. I think within that, like, the loss of self and trying to come back to self, and navigating my connection with culture, having grown up pretty white, to be honest, and what that means to me now, and as a queer person as well, where that puts me.

And so, Manuali'i is a journey and a lot of wayfinding to a place that feels grounded and whole. Able to just be yourself without trying to prove something, you know, like prove that I'm Samoan enough or queer enough or man enough or whatever it might be. Just come as you are, with everything you are and everything you've yet to learn.

Can you talk more about your Danish ancestry?

I don't know much about it, but in the late 1800s, many settlers from Norway and Denmark came over. They started, you know, colonising the land and building their huts and working on farms and, you know, gaining profit and, yeah, so that's a part of me. It's interesting because I think a lot of this journey with Manuali'i was also me acknowledging that. I felt ashamed of it, which, you know—obviously. But it's like, oh, that's a part of me too.

You know, when we talk about, like, generational curses or things that are to be broken and repaired, it's like, I think a lot of me was like, what can I do and what is my job in that, you know, given, like, things that I know now and, about where I'm from, also about the state of society and what I believe in terms of making steps towards a decolonised world? That was an interesting journey because I don't think I've ever really, like, fully leaned into it.

That is an interesting kōrero. I'm Maori and Pakeha, and there are identity markers, like, can you speak te reo Māori? Did you grow up on your marae?

I love making oka, a raw fish salad for gatherings and potlucks. I remember this one time I heard from someone from Rarotonga that they put pineapple in it, and I was like, that sounds delicious; I'm going to do that. So I brought it to this thing, and all the Samoans there were like, that's not how we do it. You know? I didn't realise it was a cultural faux pas, you know? It just sounded yummy to me. But there are so many mistakes you make on this journey, I guess. You're learning and discovering and becoming, you know?

Is Manuali'i your debut?

Yeah, it is.

So cool!

You know what? I didn't realise the work came after the writing. I felt like the writing was the work, but then it was like, ah. Oh, I have to be edited now.

”Oh, you mean I have to rewrite every poem now?” Haha. Do you want to talk about the editing process?

Finding that out and going through, you know, the things that happen when you think you're finished, when you're not. Faith Wilson at Saufo’i Press is so chill about everything. I feel blessed to have been published with Saufo’i Press and worked with her through this.

I felt no pressure, no real deadlines or timelines, so the pressure of churning out a piece of work in x amount of time wasn't on me. But yeah, I didn't realise the work after the writing. It was a whole new kind of muscle to flex—being edited. I like to dream about all things and write whimsical poetry! But editing is full stops. We had a whole conversation on full stops versus commas.

Typesetting was a whole other journey. I didn't realise the work that goes into it, looking over every edit and little detail to ensure it's exactly how you want it. I worked on the typesetting with a designer.

Have you done any studies in creative writing?

At Te Herenga Waka University, I did a 12-week paper on Māori and Pasifika Creative Writing with Victor Rodger, which was amazing. I urge anyone who loves writing and has the money and support to do that paper. It felt nice to be in a workshop environment every week and have time to write and think about writing. Having other people's feedback on my work was intentional and helpful in my practice.

At the end of the paper, I’d put together a portfolio of work, and one of Victor’s cousins is Tusiata Avia. She marked my portfolio and changed my life in writing. Like, wow. It was incredible. She went through it like an editor would, you know, cross out things and gave me feedback. And at first, you know, I had a bit of an ego death. Like, I'm never going to write again. I can't believe she read this.

Her biggest piece of advice that I've taken was to tell my story and not be afraid to take up space on the page. And instead of using words like colonisation, to tell me about your story of colonisation with that, you know. Yes. That might seem simple, but it just changed how I think about stories and how I thought about how to write. That was instrumental in finding my voice—that whole experience.

How did the publishing of Manuali'i come about?

Faith knew friends I knew and is good friends with an old flatmate of mine, Hana Aoake, who has published a beautiful poetry book - A Bathful of Kawakawa and Hot Water. And so, like, I remember going to a poetry reading, and Faith was there, reading poetry and probably having organised the whole event, to be honest, because, you know, Faith is like that.

Faith and Hana were a part of this creative collective called Tupuranga and published a digital journal. I submitted one of my first published pieces to Tupuranga, and Faith has been a champion for me ever since.

That is so cool. I remember reading the Tupuranga journal, and it was beautiful. Is the website still up?

It is. It's still there.

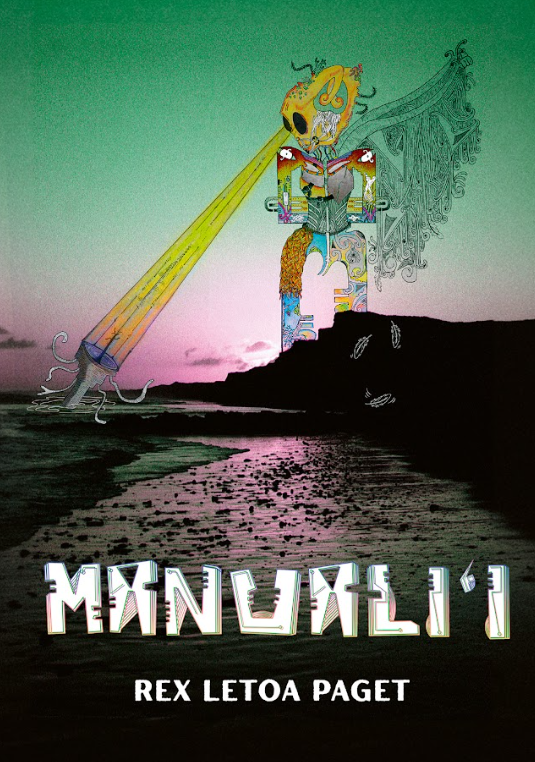

I love the illustrations on the cover and inside the book. Can you tell me more about them?

Teina Tutaki, who did the cover art and all the illustrations on the inside, is one of my best friends, like dearest friends. He keeps his artistry secret but is just a super-talented musician, artist, and thinker in general. I tapped him on the shoulder for this because I love what he does. I sent him a manuscript, and I was like, "Just go hard."

The cover illustration is on a photo of Kai Iwi beach in Whanganui, where I spent time with my dad. The illustrations are hand-drawn, including the title on the cover page, and everything is meant to be where it is. Samoan patterns throughout the illustrations represent birds, ocean, flowers, and other symbolic representations. Everything in the illustrations represents different aspects of the poems.

He didn't let me see the illustrations until we were typesetting, and I was a bit worried. I was like, what does it look like? And then it was better than anything I could ever have dreamed of. I was like, how did you come up with any of this? This is beautiful. I am super grateful for the care he took. It feels like such a gift.

Can you share the title of your favourite poem and why?

Oh, I don’t know! I think it changes.

I love the Elysian Plains chapter's first four ‘Darling’ poems. I like them because Vietnamese monk and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh had these four principles for loving someone unconditionally, which are the poem titles. I saw that and automatically thought of my dad and our relationship. Parental relationships are often tumultuous. I went off that reciprocal love and wrote poetry for my dad, you know, while he was sick and I was caring for him. That was important for me in my relationship and journey with him.

So those have always been my favourites. The poems feel soft, loving and romantic, but in a parental way, you know?

How did it feel being published? What was it like working with Saufo’i Press?

Faith is Tāmaki-based. So we had a Zoom call. She gave me an email, like, hey, this is what I'm planning, and then we kinda touched base. It was unbelievable, and I was just like, I trust you. Like, I trust you with my work. I’m 100% on board, you know. Putting my trust in someone who I feel has had my back through my creative process.

I had this unbelievable feeling about how I was going to put a book together. How do you do that? How do you have enough content? I don't know. You know? But, Faith was like, you know, no timelines. It was probably a two-year process of writing and touching base with her.

What’s next for you?

That's a really great question creatively. Now that this is birthed and out there, I want to get back to another gathering phase of putting more work together. There are other stories to tell; what do I want to tell? How do I want to tell it? And in what medium? Is it going to be poetry? Or something else, fiction or a script? I don't know. I'm figuring it out. But I'm hopeful in all my creative endeavours.

I'm still writing poetry. So, hopefully, there'll be another poetry collection, but, you know, other creative things that come my way too.

When you were talking about gathering your writing, I thought of gathering up the fishnets. Now, it's time to put the nets out again.

Yeah. That's it. It's just like, I want to feel this goodness for a little bit and then, yes, cast the net back away and see what comes in.

Manuali'i - Bird of the Gods - is an anchor to ancestors and self. These poems are reminders of who you come from and who you are, compasses to constant new becomings. Questions for timekeepers and connections to universal powers. Being guided by messengers of the sky.

Dancing on the delicate tightrope of here, the past, and an imagined future, Manuali’i dives into the heart of grief and loss and love, wraps a tongue around the soft grooves of Samoan words, and rides off into the distance on a Triumph Bonneville.